Language is useful, but not when we are trying to immerse ourselves in the world.

Psst! Join the newsletter to get the latest!

In 1933, Alfred Korzybski introduced a radical idea that would reshape how we think about thinking itself: the map is not the territory. But perhaps even more profound was his insight about the territory itself—that vast, silent realm of direct experience that exists before and beyond all our words, symbols, and abstractions. This is what Korzybski called the unspeakable world, and understanding it might be the key to escaping the linguistic traps that entangle human thought.

The World Before Words

For Korzybski, reality operates on multiple levels, arranged in what he called the "structural differential." At the base lies the submicroscopic event level—the quantum flux of particles and waves, the ceaseless dance of energy and matter that physics describes but can never fully capture. This is reality at its most fundamental: a dynamic process that exists entirely independent of human observation or description.

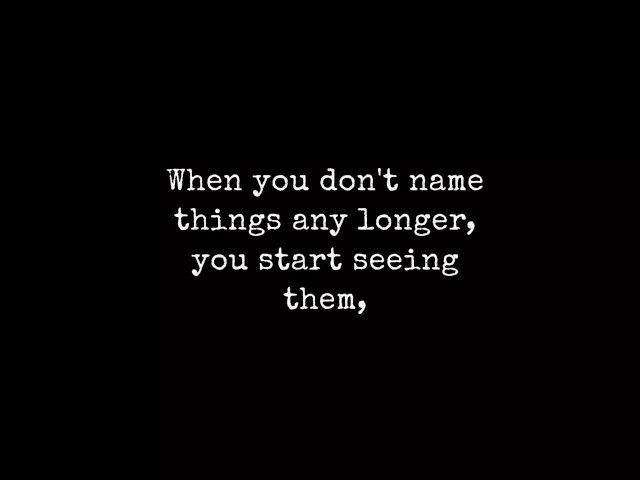

Above this sits the microscopic and macroscopic object level—the world of things we can see, touch, taste, and feel. This is the realm of direct sensory experience: the warmth of sunlight on skin, the particular shade of blue in an evening sky, the exact texture of tree bark under fingertips. Crucially, Korzybski insisted that this level of experience is inherently non-verbal. It simply is, before we name it, categorize it, or think about it.

Only after these silent levels do we reach the verbal level—the world of words, labels, and descriptions. And here's where humans routinely stumble into confusion.

The Abstraction Ladder We Cannot Escape

Every word we speak, every concept we form, is an abstraction from the silent reality beneath. When we say "tree," we're not capturing the infinite complexity of any actual tree—its billions of cells, its intricate root system, its dynamic exchange with soil and air, its history from seed to maturity. We're creating a useful simplification, a map that helps us navigate but should never be confused with the territory itself.

Korzybski saw this confusion—between our linguistic maps and the silent territory—as the source of enormous human suffering. When people argue about "democracy," "justice," or "truth," they often forget they're arguing about words, not the complex realities these words attempt to approximate. They mistake their verbal maps for the actual landscape of experience.

This becomes particularly dangerous with what Korzybski called "multiordinal terms"—words whose meanings shift dramatically depending on context and level of abstraction. "Love" means something different to a neuroscientist studying oxytocin, a poet writing sonnets, and a child hugging their parent. Yet we use the same word for all these experiences, creating an illusion of understanding where none may exist.

The Tyranny of "Is"

Perhaps no word caused Korzybski more concern than "is"—that tiny verb that creates what he saw as a fundamental delusion: the idea of fixed identity. When we say "John is lazy" or "This is good," we're engaging in what Korzybski called the "is of identity," falsely equating a complex, dynamic process (a human being, an experience) with a static label.

The unspeakable world knows no "is." It knows only process, change, and relationship. The apple you're eating isn't "red"—it's reflecting certain wavelengths of light under current conditions, wavelengths your particular nervous system interprets in a certain way. The "redness" exists in the relationship between apple, light, and observer, not as a fixed property.

This insight led Korzybski to recommend "E-Prime"—English without the verb "to be"—as a more accurate way of speaking about reality. Instead of "The movie is boring," we might say "I felt bored watching the movie," acknowledging the subjective, relational nature of the experience.

Consciousness of Abstracting

The solution, for Korzybski, wasn't to abandon language—an impossibility for symbol-using beings like ourselves. Instead, he advocated for what he called "consciousness of abstracting": maintaining constant awareness of the levels of abstraction in our thinking and speaking.

This means remembering that every word leaves out more than it includes. Every category excludes unique particulars. Every generalization misses individual variations. The word "water" tells us nothing about the specific water in this glass at this moment—its temperature, its mineral content, its journey from cloud to cup.

When we maintain consciousness of abstracting, we hold our concepts lightly. We remember that our most cherished beliefs and elaborate theories are maps, not territories. We become less likely to fight over words and more able to return to the silent world of direct experience—to what Korzybski called "first-order experiences."

The Semantic Pause

One practical technique Korzybski recommended was the "semantic pause"—a moment of silence between stimulus and response, between experience and verbalization. In this pause, we can remember the unspeakable nature of experience, the inadequacy of any words we might choose, and the levels of abstraction involved in any statement we make.

This pause creates space for what Korzybski considered the uniquely human capacity: time-binding, or learning from the accumulated experience of previous generations while remaining flexible enough to revise our maps when they no longer serve us.

Living with the Unspeakable

Korzybski's vision of the unspeakable world wasn't meant to make us give up on language or rationality. Rather, it was meant to make us more sophisticated users of these tools. When we remember that reality itself remains forever silent—that it's our nervous systems and symbol systems that create the world of words—we can use language more precisely and less dogmatically.

We can appreciate science as our best attempt to create maps that correspond to the territory, while remembering that even our most accurate scientific models remain abstractions from an infinitely complex reality. We can engage in philosophy and debate while remembering that we're ultimately discussing our maps, not the territory itself.

Most importantly, we can cultivate what Korzybski saw as sanity itself: the ability to maintain proper evaluation between our words and our experiences, our maps and our territory. In a world where people increasingly inhabit different linguistic realities—different news sources, different social media bubbles, different vocabularies—this skill becomes ever more crucial.

The Paradox of Writing About the Unspeakable

There's an inherent irony, of course, in writing thousands of words about the unspeakable world. Korzybski himself filled volumes trying to point toward what cannot be said. But perhaps this paradox itself illustrates his point: language can gesture toward its own limitations, words can acknowledge what they cannot capture, and consciousness of abstracting can emerge even through abstraction itself.

The unspeakable world remains always with us—in the pause between heartbeats, in the sensation before we name it, in the reality that exists whether we observe it or not. Korzybski's gift was reminding us that this silent territory is our actual home, and all our words are just maps we've drawn to find our way through it. The maps are useful, even essential. But the territory remains forever larger, richer, and more mysterious than any map could ever convey.

In our age of information overload, where words and images assault us constantly, Korzybski's invitation to remember the unspeakable world feels both radical and necessary. It's a call to return to immediate experience, to hold our abstractions lightly, and to maintain humility before the vast silence that underlies all our speaking. The territory doesn't need our maps to exist. But we might need to remember the territory to preserve our sanity in a world made of words.